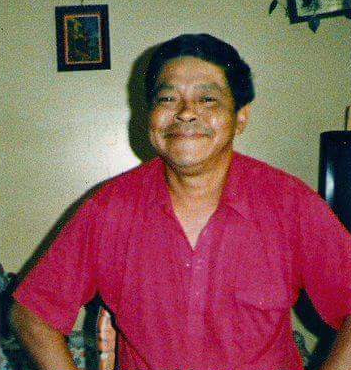

Told by his son, Frank Jr.

My father, Frank James Watts, was arrested by the police at a Safeway in Prince Rupert. My dad was intoxicated to a point of semi-consciousness at the time, yet the two arresting officers were seen roughly handcuffing my dad and throwing him into the back of a police vehicle.

By the time my dad reached the police station, he was unconscious. The two police officers carried my dad into the police station while his hands were still handcuffed behind his back. Although police policies dictate that any unconscious individuals under arrest should receive a medical exam before incarceration, my dad was not provided with this life-saving practice.

Though the official RCMP and Coroner’s reports state that my dad was placed in the recovery position within the drunk tank, several of my dad’s fellow inmates have said that he was placed on his back. As my dad’s official cause of death was “asphyxia as a result of obstruction in the airway by gastric fluid content,” I am not sure how my father could have suffocated on his own vomit if he had been in the recovery position. Furthermore, the other inmates called for help when my dad started to vomit, but the responding civilian guard was unable to enter the drunk tank without an RCMP officer. Thus, the civilian guard closed the cell door without turning my dad on his side, which could have saved his life. The RCMP are responsible for the proper training of civilian guards who work within correctional facilities, but this particular guard did not have the appropriate training to perform his job correctly.

The most devastating aspect for me is that my first cousin, Leonard Watts Jr., witnessed my dad’s arrest and followed him to the police detachment to try and take my dad home. Though it is the law that the police must release publicly intoxicated persons when they have “sufficient capacity to remove themselves without danger to themselves or others or causing a nuisance” or sooner if a capable adult comes to take charge of them, the RCMP denied my cousin’s request of release (Offence Act, s91(3)). My cousin was sober and 29 years old, a fully grown adult. I do not understand why he was not deemed “capable” of taking charge of my dad.

The day after my dad died in police custody, I called the police department to find out what had happened. The Police Chief offered to pay for my dad’s funeral but I was uninterested in accepting his offer until I found out what exactly happened to my dad. I was shocked to find out that the Corporal who had been presiding over the detachment at the time of my father’s incarceration also led the investigation into his death. The RCMP reviewed the Corporal’s investigation and found that the conflict of interest his position presented had not affected the validity of his findings.

My dad’s asphyxiation resulted for several reasons. First, the RCMP surveillance policy at the time did not require the civilian guards to note whether or not they had physically (in-person) or remotely (through CCTV footage) checked on the inmates. The civilian guard on duty could not recall whether he had physically or remotely checked on the drunk tank inmates. If he had only checked on my dad remotely, it would have been impossible for him to determine my dad’s physical state. I was provided with a copy of the CCTV footage and found that my dad was not visible on the recordings; the cameras were angled so that the only visible body part of the upright inmate was their head. Since my dad was lying on the floor, he was not within the view of the cameras.

Second, the autopsy report showed that my dad had petechial hemorrhages on his scalp, which is consistent with bruising. My dad also had diffuse hemorrhages around and within his right eye, which could also demonstrate bleeding and bruising. Due to the witness testimonies I received from bystanders present at my dad’s arrest, I believe that my dad was handled roughly by the RCMP upon his arrest. Some of the RCMP’s physical manipulations of my dad’s body may have led to head trauma that resulted in his loss of consciousness.

Third, the autopsy report states that my dad had “edema fluid in the lower tracheobronchial tree” and “pulmonary edema in the lungs”, indicating excess fluid in his lungs. The resuscitation paramedics present at my dad’s death also noted large amounts of gastric fluid from the lungs during chest compressions. Each of these factors demonstrate that my dad died from choking on his own vomit, which should not have been possible if he was in the recovery position.

When my dad died, the coroner assigned to his case, John McNish, told me that my dad did not have enough alcohol in his system to kill him and that my dad’s heart issues were not severe enough to have played a role in his death. McNish assured me that I had a 100 percent chance of winning a lawsuit against the RCMP.

However, McNish was replaced as coroner shortly thereafter. The second coroner did not include many of the details that McNish pointed out to me and of which my lawyer has photographic evidence, such as the dark bruises on my dad’s temple and above his nose. I believe this to be a coverup.

Racism had a hand in the death of my dad, Frank James Watts, as many First Nations have been and continue to be neglected and at risk of death at that Prince Rupert police department. Even though the Coroner’s Report made many recommendations to help avoid similar incidents in the future, I have not seen evidence of any changes to their policies. Unfortunately, this systemic discrimination is not just a Prince Rupert issue. I, myself, have two uncles who have also died while in police custody in BC.

I have been unable to get legal help for my dad’s case, though I have approached over 20 lawyers. I later realized that at the time of my Dad’s death, my siblings and I were grown adults and were not considered financial dependents. Therefore, I had no recourse under BC law, because my dad’s life was worthless. The RCMP were free to neglect and kill my dad without any sort of accountability under provincial legislation.

Prior to my dad’s death, I was a youth worker and a vibrant contributor to the community, and following these terrible events I ended up becoming lost in addiction because I was so angry and suddenly my life seemed so hopeless.

With help from the Union Gospel Mission, I’ve now been clean and sober for the past four years and have been working very hard to get my life back on track. I’ve nearly completed a bachelor’s degree in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Simon Fraser University and hope to thereafter earn a Master’s in Environmental Science. I am looking forward to enacting positive changes in British Columbia. I want to get justice for my dad and anyone else who died wrongfully in police custody.

I reached out to The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society because I wanted my dad’s story told and my voice to be heard. So many people in the First Nations community are afraid to come forward, or have been completely defeated by the system, and don’t feel that justice is even possible. My three brothers, three sisters, and nieces and nephews were severely traumatized by what happened to my dad.

I want to carry the torch forward in order to set an example for my community, so that I can work for positive change, access to justice, and accountability for wrongdoers. I pray with all my heart that justice will be served and these inhumane laws changed.

‘In Their Name’ is the campaign of ‘The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society’ – a BC registered non-profit organization comprised of volunteer families who have lost a loved one to wrongful death in BC and were denied access to justice. In response to the biggest human rights issue facing the province today, our goal is to modernize British Columbia’s antiquated wrongful death legislation, which predates confederation (1846). Under current legislation, the value of a human life is measured only by the deceased’s future lost income, so long as they had dependents.

‘In Their Name’ is the campaign of ‘The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society’ – a BC registered non-profit organization comprised of volunteer families who have lost a loved one to wrongful death in BC and were denied access to justice. In response to the biggest human rights issue facing the province today, our goal is to modernize British Columbia’s antiquated wrongful death legislation, which predates confederation (1846). Under current legislation, the value of a human life is measured only by the deceased’s future lost income, so long as they had dependents.