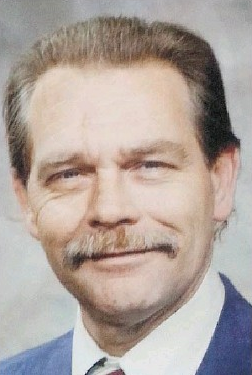

Told by his son, Jeff

“My father, David Fast, was a real character with a wild sense of humour. He was a remarkable man who sadly lived with very difficult to control, brittle Type 1 Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus as well as over 10 other chronic and life-threatening conditions. Despite his poor health, my father always fought to live the best life he could. I, and my two sisters, miss him dearly.

My father died at the young age of 55 on July 27, 2013, at 11:16 PM. He suffered cardiac arrest at North Fraser Pretrial Facility and fought valiantly during his transfer to Eagle Ridge Hospital and then Royal Columbian Hospital, where he eventually lost his life. My father died from a severe case of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) that was entirely preventable. A lack of communication and an utter disregard for patient care among medical professionals, arresting officers, correctional officers, and legal authorities prevented my father from accessing insulin; his low insulin levels led to a Diabetic Vascular Disease Leg Blockage that directly contributed to his fatal heart attack.

At the time of his death, my father possessed over 20 different prescriptions due to his many psychological and physical illnesses. He was diagnosed with brittle Type 1 Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus, Retinopathy, Peripheral Disease, Cardiomyopathy-IHD, Cardiovascular Disease, Intermittent Explosive Disorder, Paranoid Schizophrenia, a range of personality disorders, Depression with Psychotic Features, Cognitive Impairment, Hypoxic Brain Injury, and Antisocial Personality Disorder, to name a few. My father was also deemed to have cognitive deficits consistent with dementia. Accordingly, he was labelled as an acute, chronic patient who was unable to self-manage his insulin levels or properly administer his own medications. My father’s doctors told me that he would not survive if he lived alone, on the streets, in prison, or in a shelter.

Before his arrest, my father suffered three traumas to the head as well as two strokes. The first trauma on June 19, 2012, resulted in a broken clavicle and lacerations on his face and forehead. The second trauma on June 23, 2012, caused him to lose consciousness and develop a hematoma lesion on the back of his head. The third trauma, on June 29, 2012, produced a re-broken clavicle and a minor brain injury to his frontal lobe. On October 16, 2012, my father had a major stroke that kept him in a medically-induced coma for several weeks. Each of these incidents affected my father’s ability to monitor his insulin levels, to properly care for himself, and to effectively advocate for his needs.

After his second stroke, my father recovered at Timber Creek Tertiary Care Facility (Timber Creek). The doctors there failed to officially log all of my father’s diagnoses on PharmaNet or to communicate with the doctors who provided his past diagnoses. They also wrote a prescription for my father after he left their facility on July 17, 2013. As a result, any other medical professionals who treated my father in the future would not be able to access the results of his treatment at Timber Creek.

The day of my father’s release from Timber Creek, he was sent to Langley Memorial Hospital with severe hyperglycemia. He remained there for one week before being released on July 23, 2013. Upon his release, he decided to come to Chilliwack and visit me. Unfortunately, I was unaware of his intentions.

On his way to visit me, my father was picked up by the Chilliwack RCMP and placed in a holding cell. That same day, July 25, 2013, he was transferred to North Fraser without a C-13, the form that would note any pertinent information about his well-being. This C-13, which was not delivered to North Fraser until the day after my father’s transfer, read, “unstable, lethargic, vomiting, and angry prior to transport.” My wheelchair-bound father was without his prosthetic leg, medication, insulin, and medical bracelet.

During his time at both the Chilliwack RCMP and North Fraser, my father was incontinent and thus was soaked in urine. Though I am told that he was given several new sets of clothing and opportunities to clean, he was nude in the video footage documenting the last four hours of his life. For the three days that my father was at North Fraser, he received no medicine or insulin and consumed nothing other than water and juice. Additionally, the officers at North Fraser did not refer to VISEN, the information system used by BC Corrections to inform other facilities about inmates’ various behavioural attitudes and medical conditions. Perhaps if they had accessed VISEN and learned of my father’s diagnoses, he would still be here.

When I found out that my father was incarcerated, I informed the Duty Counsel of my father’s many health conditions and needs. The Duty Counsel assured me that my father would be sent to the hospital to receive proper care. In reality, my father was put in a holding cell and not sent to the Health Care Unit, as the physician at Sentry Health asked the nurse to do. Instead, the nurse went home, and the physician called a doctor who had never treated my father, thus failing to secure my father’s relevant medical history and treatment plan.

On July 26, 2013, my father was supposed to attend Chilliwack Courthouse but he was in extreme pain, as his body was shutting down without his essential medications. My father was gulping water, complaining of extreme thirst, unable to control his bladder, vomiting, screaming, crying, pounding on his cell door, flailing his arms, and speaking to himself. He was also experiencing slurred speech, lethargy, delirium, incoherency, random and extended periods of drowsiness, and an inability to stay awake as he drifted in and out of consciousness. His leg was so purple, swollen, and poorly perfused that he was unable to stand. Yet, the paramedics were not called, and my dad was put back in the holding cell where he would have his first bout of cardiac arrest the next day.

In my father’s obituary, I stated that he died from a heart attack because that was what the coroner had said caused his death. However, a subsequent coroner’s inquest and autopsy report informed me that my father died from a severe case of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (63 mm/ol at time of death). Diabetic Ketoacidosis fit perfectly with the symptoms my father had been experiencing for the two days before his death: vomiting, dehydration, polydipsia (excessive thirst), polyuria (excessive urination), fatigue, changes in behaviour, and decreased levels of consciousness.

While trying to seek justice for the abominable treatment my father received in our legal and medical systems, I was stalled. Firstly, I was almost unable to receive a proper autopsy for my father. When I called to request one, I was told that my father was about to be cremated—without my knowledge or consent. Secondly, the BC Ministry of Attorney General confirmed my belief that the North Fraser recording system had only captured the last four hours of my father’s three-day confinement. I received conflicting explanations as to why there was not further footage; I was told both that the rest of the film had been taped over and that the system had crashed, only to be restored for the final four hours of my father’s life. The Chief Coroner of British Columbia admitted that my father’s coroner had failed to secure the video recordings in a timely fashion and that these video recordings would have undoubtedly assisted in determining the circumstances surrounding my father’s death. Thirdly, the day that the Chilliwack RCMP picked up my father, there was video footage of him speaking to the RCMP officers. The video did not have any audio, but the Chilliwack RCMP rejected my request to conduct a forensic examination for the purpose of discovering what my father was disclosing.

Furthermore, the coroner stated that my father’s third traumatic brain injury was accidental, though the medical records said differently. I found out after the fact that his injury was caused by a robbery and assault. The head trauma he received in this attack was an underlying cause of his major stroke, which exacerbated his inability to surmise his insulin levels and live alone.

After my father’s death, the Coroner’s Office made several recommendations to Correctional Facilities about health care, due process, and protecting medically- and psychologically- vulnerable individuals. And while I am glad that “apparently” future inmates will not experience the same traumas my father did, I still believe that more should be done to avenge what essentially amounted to be my Dad’s death.

I came to learn that since my father had no income or dependents, his life had little to no value under BC provincial legislation that deals with wrongful deaths. He was a very vulnerable human being with numerous medical conditions, who was essentially medically and nutritionally neglected to death. He was wrongfully killed, but there is little to no recourse for me or our family under BC law. The full measure of justice that would be afforded to our family in other jurisdictions in the developed world is not available here in British Columbia, and there is little to no accountability for my Dad’s death.

I connected with The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society because I know my father’s story needs to be told. I hope one day these laws will change from protecting the wrongdoers to protecting the victims. Maybe then we will be able to put an end to all this and gain justice for my father.”

Media Coverage

BC Government news release: Inquest announced into death of David Edwin Fast

‘In Their Name’ is the campaign of ‘The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society’ – a BC registered non-profit organization comprised of volunteer families who have lost a loved one to wrongful death in BC and were denied access to justice. In response to the biggest human rights issue facing the province today, our goal is to modernize British Columbia’s antiquated wrongful death legislation, which predates confederation (1846). Under current legislation, the value of a human life is measured only by the deceased’s future lost income, so long as they had dependents.

‘In Their Name’ is the campaign of ‘The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society’ – a BC registered non-profit organization comprised of volunteer families who have lost a loved one to wrongful death in BC and were denied access to justice. In response to the biggest human rights issue facing the province today, our goal is to modernize British Columbia’s antiquated wrongful death legislation, which predates confederation (1846). Under current legislation, the value of a human life is measured only by the deceased’s future lost income, so long as they had dependents.