A 2017 report by University of Ottawa Economics Professor Rose Anne Devlin ‘Comparing Insurance Across Canada‘ provides a detailed analysis of auto insurances regimes in our country.

Our ‘Coles Notes’ are as follows…

The respective jurisdictions are grouped as having a privately-provided automobile insurance regime (Alberta, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Prince Edward Island) or a publicly-provided one (British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec).

In addition, four provinces have No-Fault provisions (Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec) – the first three have ‘partial’ regimes whereas Quebec has ‘pure’ No-Fault (no recourse to the courts for damages).

Of the four public insurance provinces, three have No-Fault regimes. Manitoba and Quebec do not allow any suits for pain and suffering, and Saskatchewan imposes a $5,000 deductible on awards for pain and suffering (since 2003, Saskatchewan has allowed drivers to opt out of No-Fault provisions, but this is rarely done). Manitoba and Saskatchewan would be considered as ‘partial’ No-Fault regimes as the right to sue for economic losses in excess of No-Fault benefits is maintained. By contrast, Quebec has a pure No-Fault system for all road accidents involving bodily injuries. This means that Quebecers cannot resort to the tort system to sue for additional damage recovery.

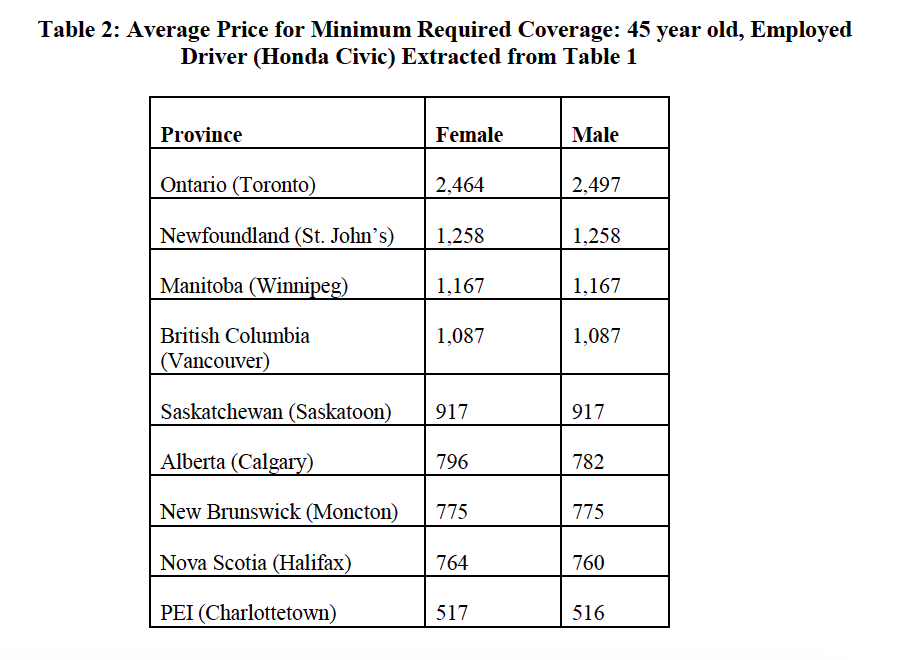

Automobile Insurance Pricing Across Canada Circa 2017

High risk drivers, who cannot obtain automobile insurance through conventional means, have to apply to a Facility Association which provides them with coverage typically by facilitating a risk pooling contract across several companies. Facility Associations exist in all privately provided automobile insurance regimes because automobile insurance is mandatory. Not only is the information from these high risk drivers exempt from GISA data, but so too is information from uninsured drivers. The Facility Associations have an uninsured motorist fund that indemnifies victims of uninsured drivers. Thus GISA data does not include all of the very high risk portion of the driving population.

One interpretation of this observation is that the public regimes are outperforming the private ones insofar as their claims are closer to earned premiums – but this is too facile an interpretation for the reasons already stated. Moreover, because public regimes may have more ready access to other sources of revenue typically not available to private companies, including fees for a variety of other, related, services, like drivers’ permits and vehicle registrations, not to mention the possibility of transfers from general government revenues, this means that they can operate with a higher loss ratio relative to the private regimes. Another reason why public regimes may have a higher loss ratio is because their data include all of the high risk drivers – those who would have to resort to a Facility Association in the private regimes, plus those who drive uninsured.

Our takeaways are as follows…

Ontario is definitely the most expensive in Canada as of 2017. However, private insurers typically have higher mandatory minimum insurance coverage amounts. They also have the highest adjusted average per claim costs (more than double BC). They do not have access to various licensing fees, vehicle registrations, etc. for revenue that the public insurers have. They don’t get bailed out by government so they cannot operate with thin margins. Ontario has the highest population density, which results in more collisions. They also have the provisions of No-Fault despite being private. Statistically, crashes increase after the implementation of No-Fault regimes. Alberta is private, does not have No-Fault, and it has some of the lowest cost insurance in Canada.

The biggest comparison from that analysis when looking at the future of automobile insurance in BC under No-Fault would be Manitoba. Our Easternmost Prairie province has a No-Fault regime with a public insurer that was still more expensive than ICBC, as of 2017 for the average driver utilizing the same insurance.

Manitoba also has double the motor vehicle casualty rate as British Columbia, as per the Government of Canada Traffic Statistics website.

Canadian Traffic Casualty Rates – 2018

One might speculate that No-Fault might actually make our roads less safe without having general deterrence mechanisms and incentives in place to make its roads safer for motorists, passengers, pedestrians, and cyclists alike!

One might also argue that if the No-Fault scheme is implemented in BC, policy holders will likely save money at first on their premiums. However, with nearly 6,000 employees, ICBC has roughly twice the amount of staff compared to any other Canadian insurance provider its size. As a result, ICBC’s high overhead directly inflates auto insurance premiums. Other insurance providers provide the same services more efficiently across the country. Consequently, the government’s inability to restructure ICBC, as well as lacking focus on root cause prevention as per the 2016 Vision Zero Road Safety Strategy, will inevitably lead us down the road to the same financial problems years from now. Except at that time, there won’t be anymore victim rights to take away to counterbalance poor management and decision making.

‘In Their Name’ is the campaign of ‘The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society’ – a BC registered non-profit organization comprised of volunteer families who have lost a loved one to wrongful death in BC and were denied access to justice. In response to the biggest human rights issue facing the province today, our goal is to modernize British Columbia’s antiquated wrongful death legislation, which predates confederation (1846). Under current legislation, the value of a human life is measured only by the deceased’s future lost income, so long as they had dependents.

‘In Their Name’ is the campaign of ‘The BC Wrongful Death Law Reform Society’ – a BC registered non-profit organization comprised of volunteer families who have lost a loved one to wrongful death in BC and were denied access to justice. In response to the biggest human rights issue facing the province today, our goal is to modernize British Columbia’s antiquated wrongful death legislation, which predates confederation (1846). Under current legislation, the value of a human life is measured only by the deceased’s future lost income, so long as they had dependents.